About

Realism has a long and deeply loved place in art history. When the Egyptian mummy portraits from Fayum, which were made sometime around the first century BC, were discovered, they became a huge sensation. How about that for transcendental eye contact! In all likelihood, they represent the oldest known attempts at evoking the dead in the corporeal world by realistically painting their likeness. These paintings served a ritual function, and were executed using a particular wax technique on a wooden board that was placed next to the fabric used to wrap the dead. Perhaps the same ritual meaning, passed down through the millennia, recurs in the family portraits of Martina Müntzing.

Her new exhibition at CFHILL, her first major retrospective, features seven paintings. All of them are portraits, in one way or another. The centrepiece of the exhibition is the most recent of the works; a self-portrait of the artist standing by a body of water with her husband. It constitutes a clear nod to the romantic nationalist painter Richard Bergh’s Nordisk Sommarkväll [Nordic Summer Evening] from 1899, which is on display at the Gothenburg Museum of Art. A man and a woman, garbed in the casual elegance of the bourgeoisie, stand on a balustraded porch, leaning against a wooden pillar. The people in Bergh’s painting bear a striking resemblance to the Müntzing-Arrhenius couple.

In Müntzing’s painting, the crisp, white ball dress has been replaced by a white, paint-stained artist apron. Like the woman in Bergh’s work (the singer Karin Pyk), her hair is tied back, and her arms held in a defiant yet vulnerable gesture, clasped behind her back in a way that causes her chest to jut out. In the contemporary work, the man in Bergh’s painting (Eugen, the painter prince) is represented by her husband, who is maintaining the same, rather rugged posture, with his arms confidently crossed over his chest. However, the similarities end there.

While the cool Nordic light and the architectural framing of Bergh’s work grant the painting a safe, homely mood, Müntzing’s painting is dominated by a scorched[JS1], white nothingness, as though it were locked in a struggle with the physical entities within the image. The whiteness seems to be threatening to consume the horizon, along with the two figures, who are seemingly able to carry on existing only by being anchored in place by a viewer.Another significant detail is the way the balustrade in the older painting constitutes a clear border between the plane on which the couple is standing and the water. In Müntzing’s painting, there is hardly even a suggestion of the presence of water. The water emerges as a mere idea, a convention, and the rickety jetty leads right down into the unknown.

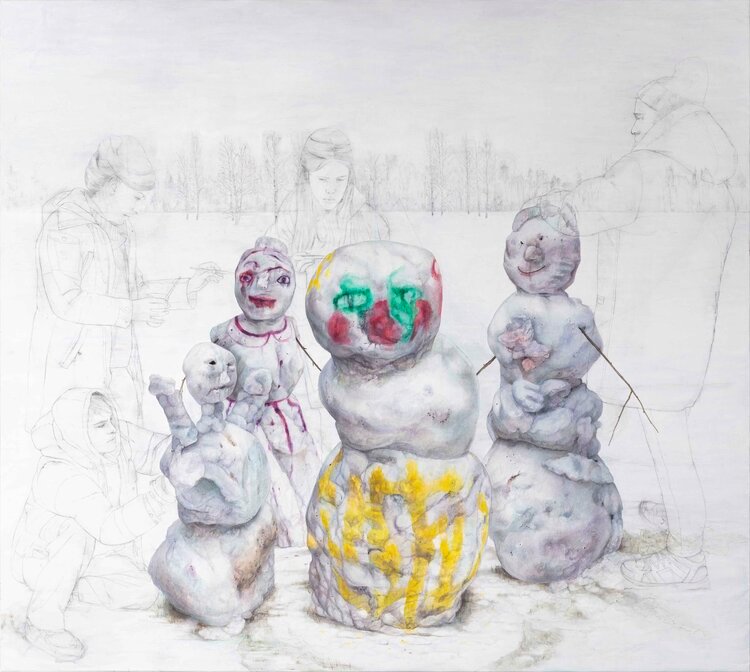

Martina Müntzing’s painting expresses a deep obsession with time. This subject first enters the works through the slow, meticulous approach she permits herself to take. Never is there a visible brushstroke to be found. A brushstroke is, after all, an account of time, in a way. By letting the work take time, and letting each single square millimetre gradually emerge and constitute its own separate microcosm, she seems somehow to freeze time. The melting snowmen in one of her most recent paintings thus become paradoxical. Caught, as they are, in a moment between existences, between solid form and the translucency of melted water, they too represent frozen time. Beyond the image, they would soon fall apart.

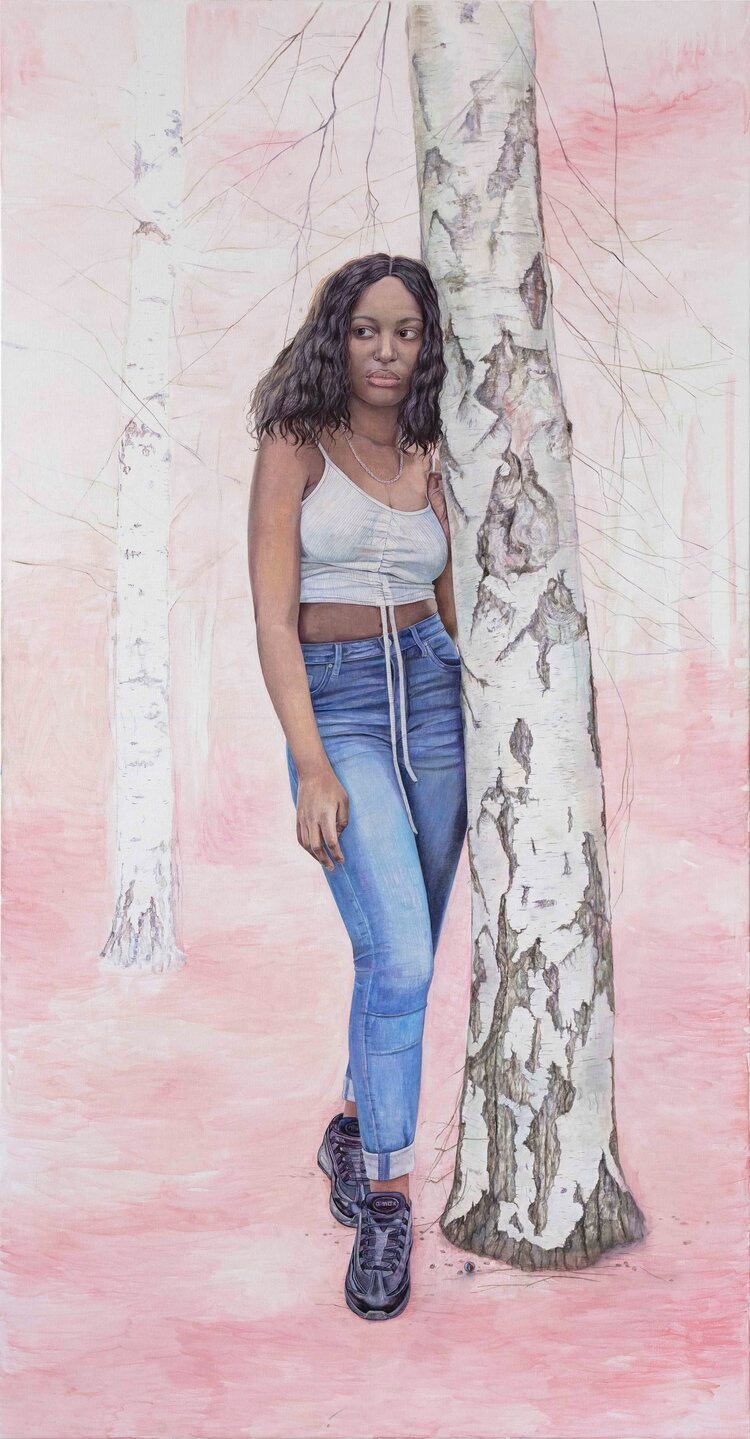

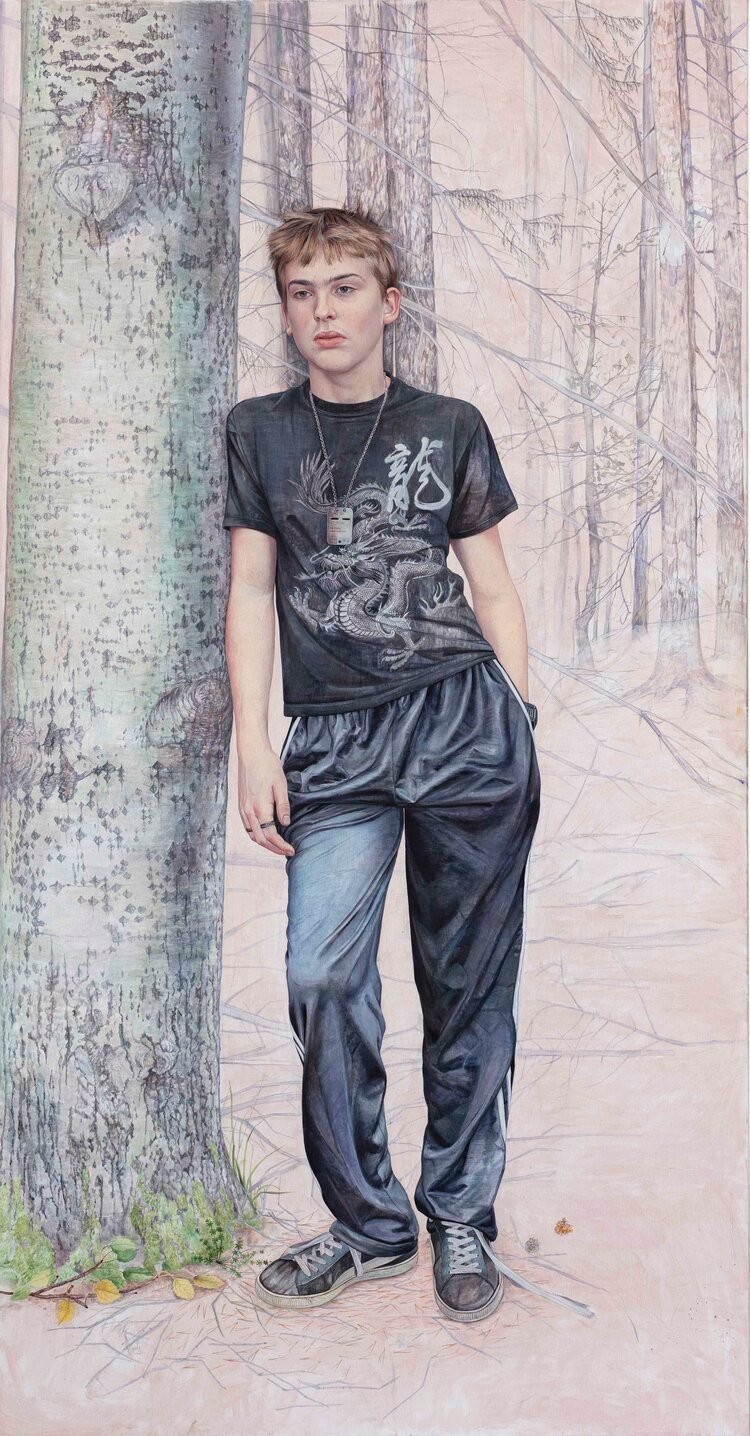

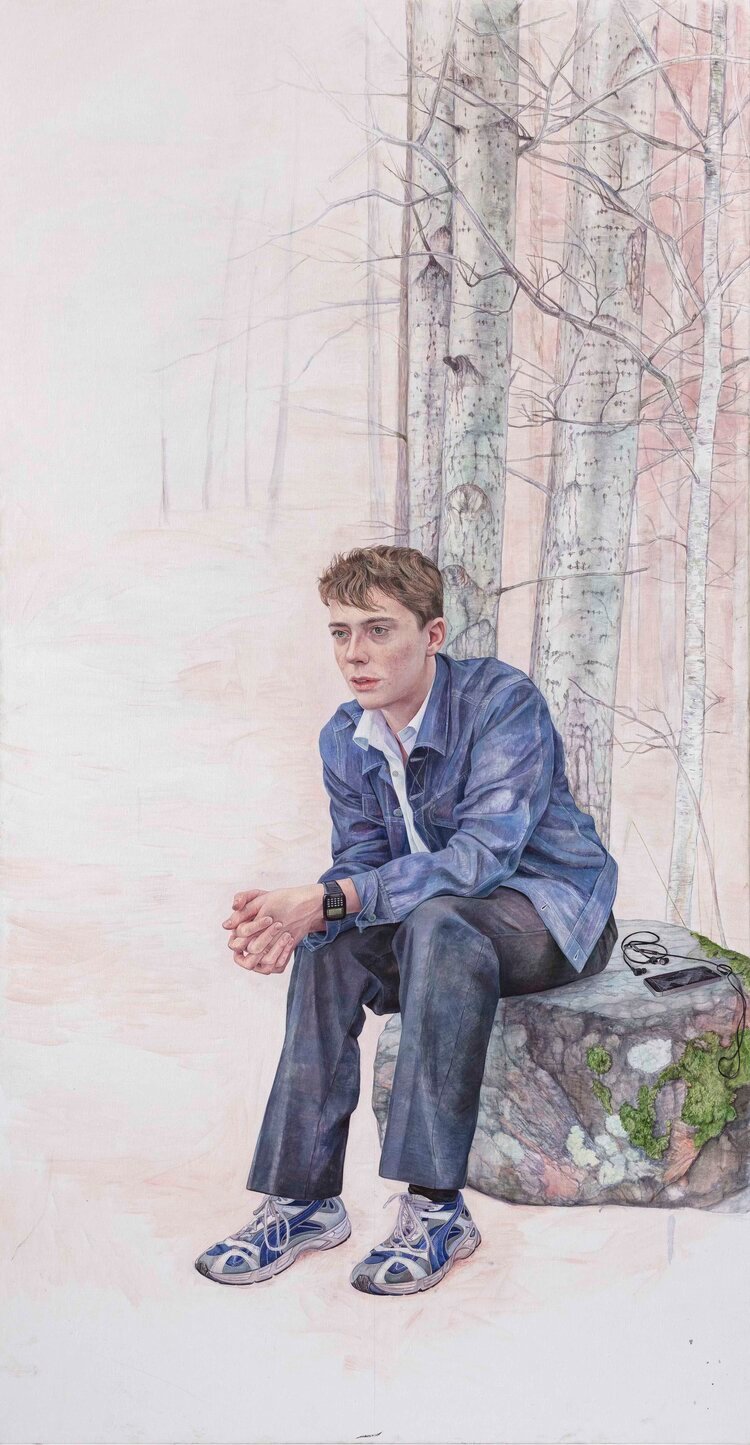

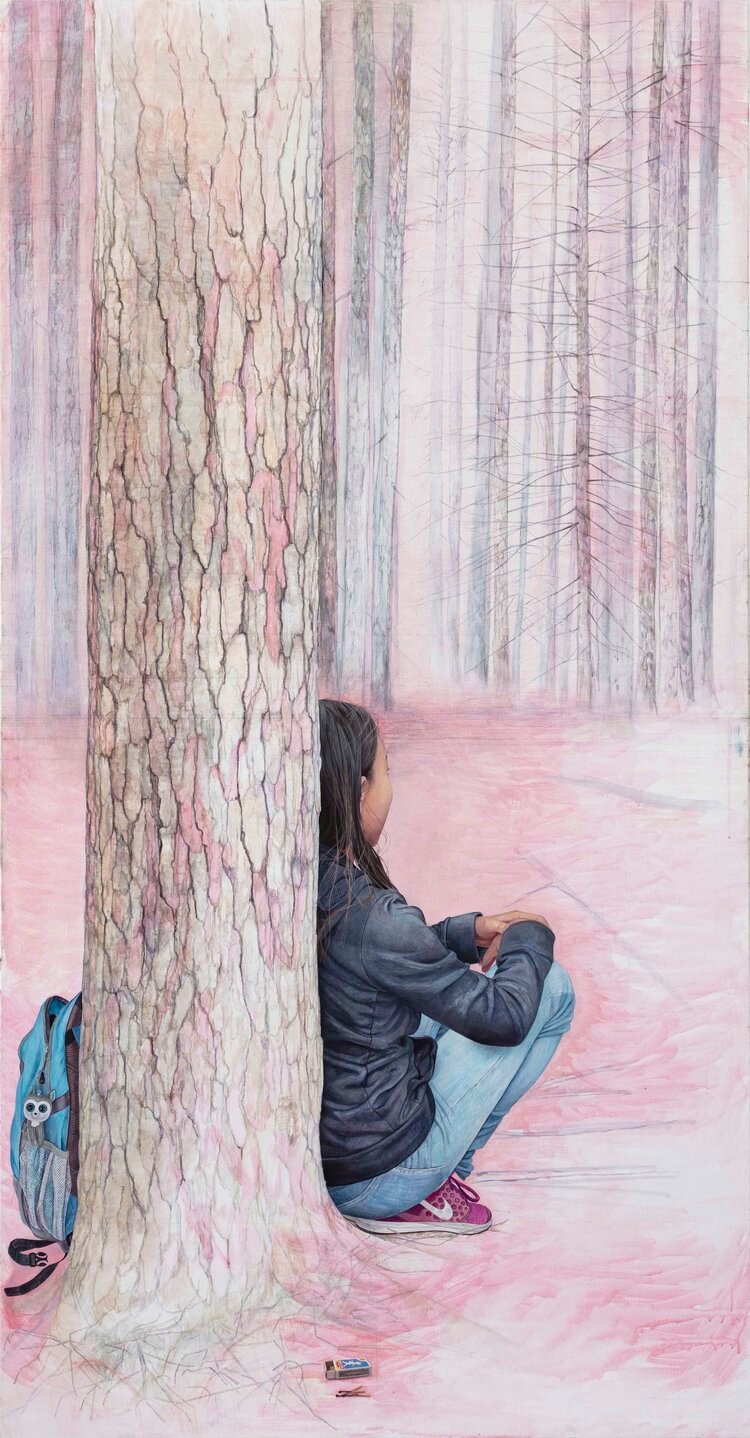

Throughout her oeuvre, Martina Müntzing has painted children, both her own and others, most likely their friends. In her most recent series of paintings, they have become teenagers, grown to their full height, but still carrying traces of their childhood selves in their facial features. Each child leans against a tree. Although this painting is entirely realistic, almost done to scale, even, as though the painter were consumed by a manic desire to stick to the truth and nothing but the truth, it still retains a quality of the mysterious. Is it a forest, or, rather, somewhere beyond time and space, a quantum cranny along the wondrous arc of relativity? The children’s gazes encapsulate both the past and the promise of the future.

Martina Müntzing’s exhibition marks out its own territory within the history of Swedish painting. There is a kinship here with Fra Angelico of the Early Renaissance, Caspar David Friedrich of the Romantic Era, the family painter Carl Larsson, and the decorative mystique of folklore. It is this band of faithful proponents of the possibilities of painting she has joined with in taking her place as one of the greats of our own time. It is a great pleasure and honour to be presenting her first exhibition at CFHILL