About

Eva Klasson – From the Moon and Back

Le troisième angle, created during a few months in the mid-70s, have since become iconic keystones of photographic art history, and core elements of the impressive photographic collections of Moderna Museet. A few years later, another innovator and breaker of new ground within the expanding fields of postmodernism and art began to use her own body to achieve a shift in the habits of seeing: object – subject. Her name was Cindy Sherman, and the pictures were Film Stills (1977–1980). But Eva Klasson did it first. Here’s her story.

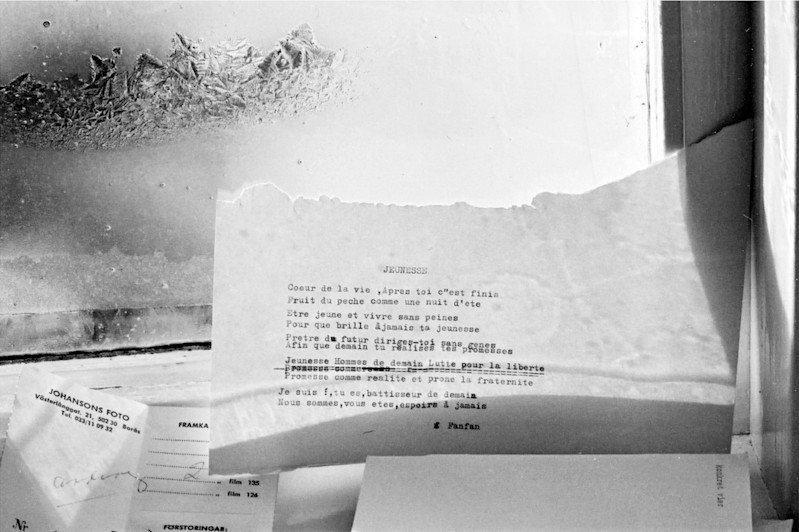

It was the magical summer of 1969, and in a dark room in Gothenburg, a woman in her early 20s was developing the pictures an entire world was waiting breathlessly for: the photographs from the moon. The crew of Apollo 11 brought along a Hasselblad camera, and soon, millions, perhaps even billions, would finally get to glimpse something that humanity had dreamed about since the dawn of time. To get to see something nobody had seen before. But nobody, not even Eva Klasson, as the young woman was called, knew that she would soon be in a different dark room, this one in Paris, developing pictures she had taken herself, of herself. This time, the exploration would be of a territory that most probably expected to be fully charted, but which would prove to house whole undiscovered worlds. These pictures would redefine photography, liberating it from controlled documentation to the existential, the immediately experienced. The third angle.

Eva Klasson was born in the rural outskirts of Borås in 1947, and began to dream of a career in photography at an early age. This was during the golden age of the weekly magazine, with their glossy pages of black and white photographs of long-legged models, gorgeous actors, and horrific visual reports from famines and war in distant lands. She found work as an assistant for various photographers and learned the fundamentals of the craft. After a while, she was thought to be skilled enough to apply to the most prestigious school for all those who dreamed of working as photographers: Fotoskolan in Stockholm, which was founded by Christer Strömholm and Tor-Ivan Odulf.

I stayed for three weeks. After that, I’d had enough. I wasn’t happy there, and I didn’t want to be there.

And that was that. She never actually met with Strömholm, the master, during those short weeks. But they would soon meet again, in rather surprising circumstances: as equals, rather than as master and student.

After leaving the school in a hurry, she ended up in Gothenburg, at the Hasselblad factory, where she developed the pictures from the moon. (“When Hasselblad himself was home, he would fly his flag!”). Some friends decided to get a jeep and drive down to Paris, and she tagged along. She embarked on a new chapter of her life with 1,000 kronor in her pocket and her Nikon hanging off of her shoulder. In Paris, she lived the bohemian life, and everything was new: new friends, a new language. Among many new encounters, a truly remarkable one occurred.

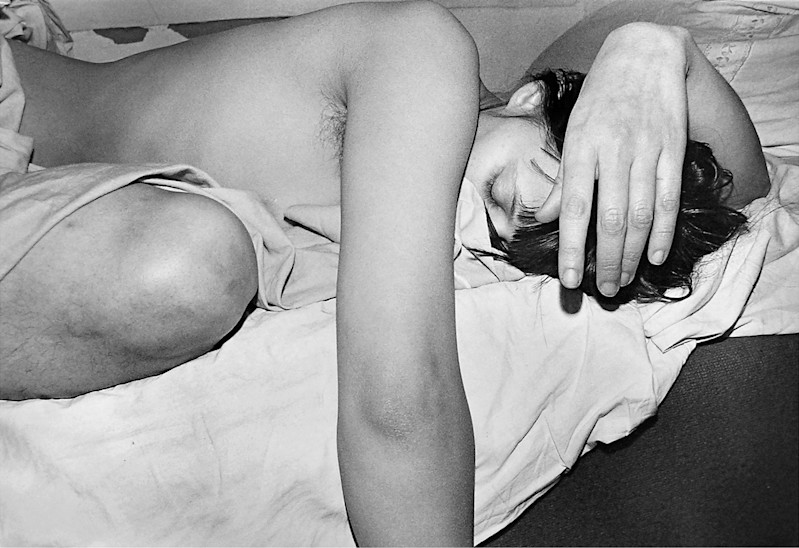

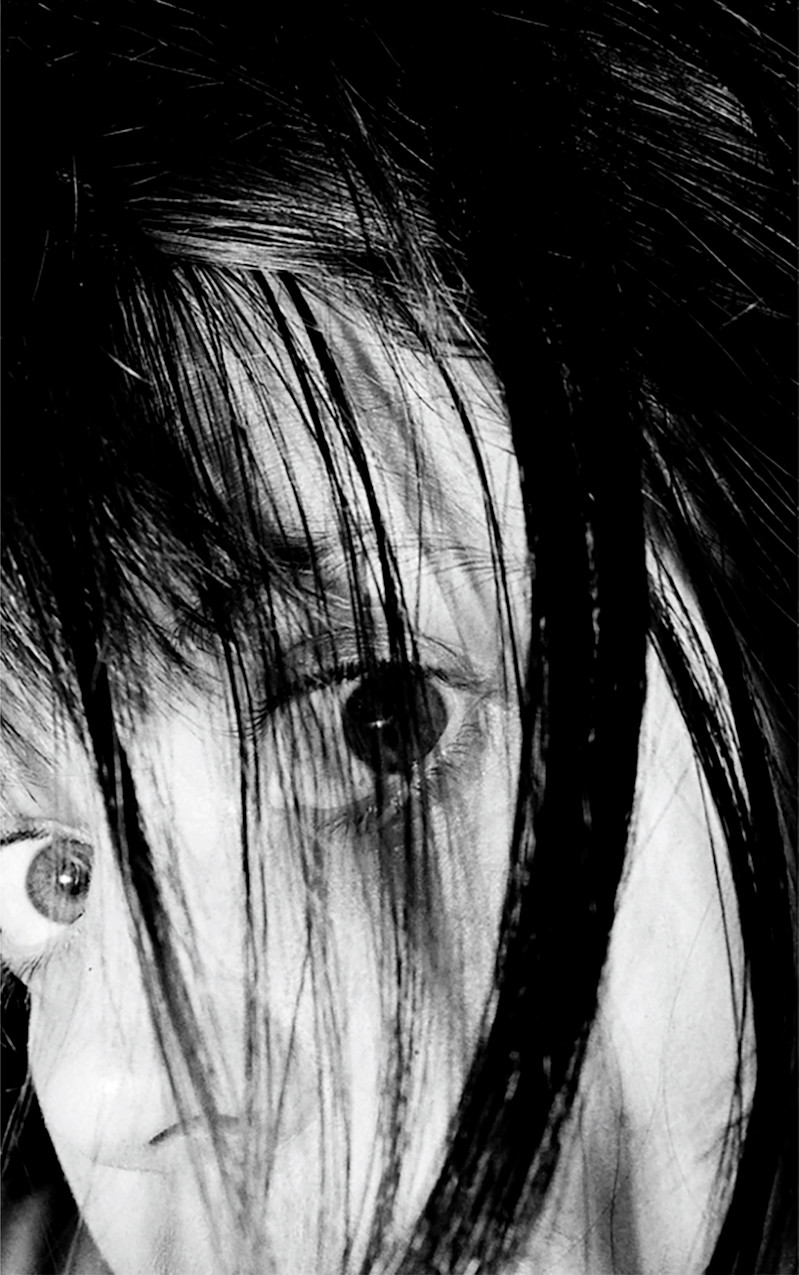

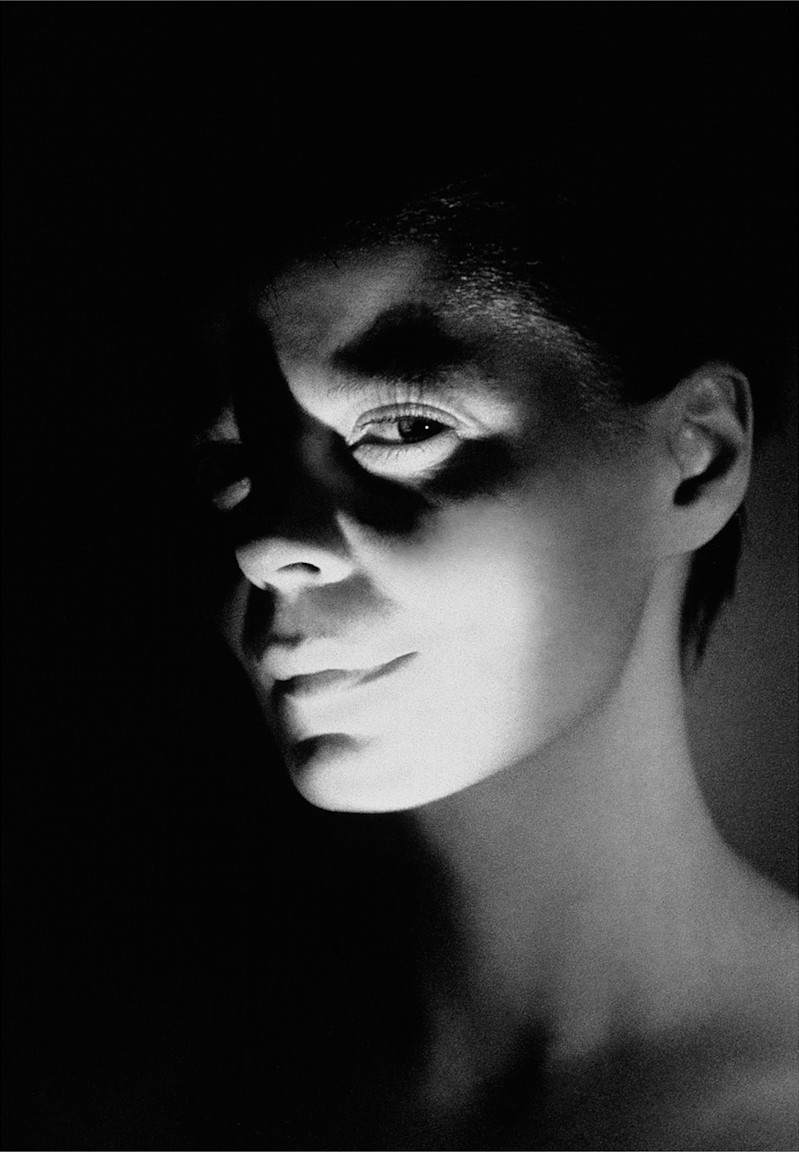

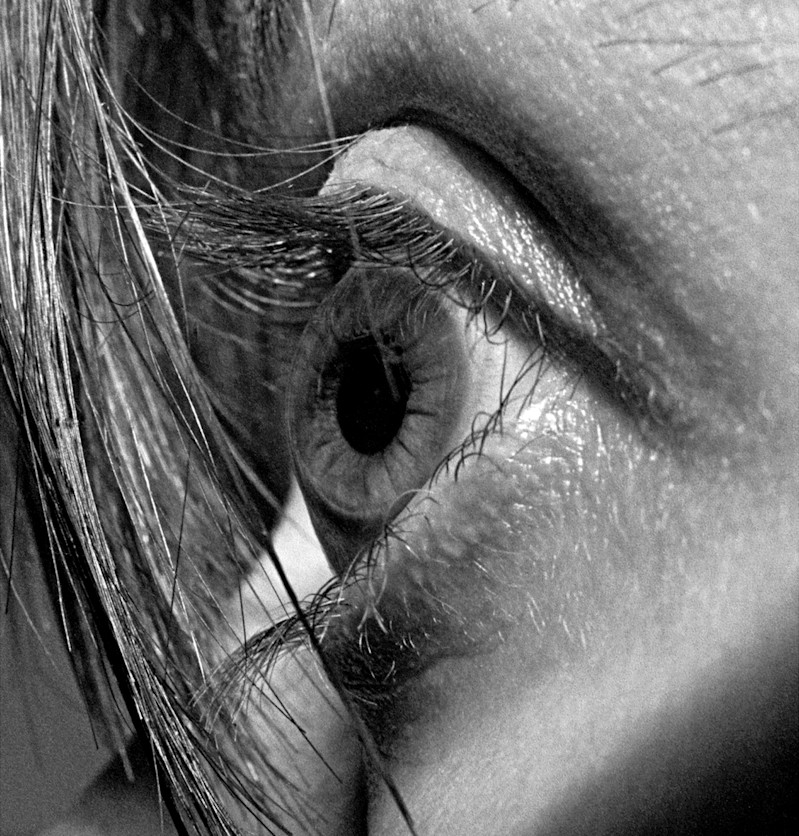

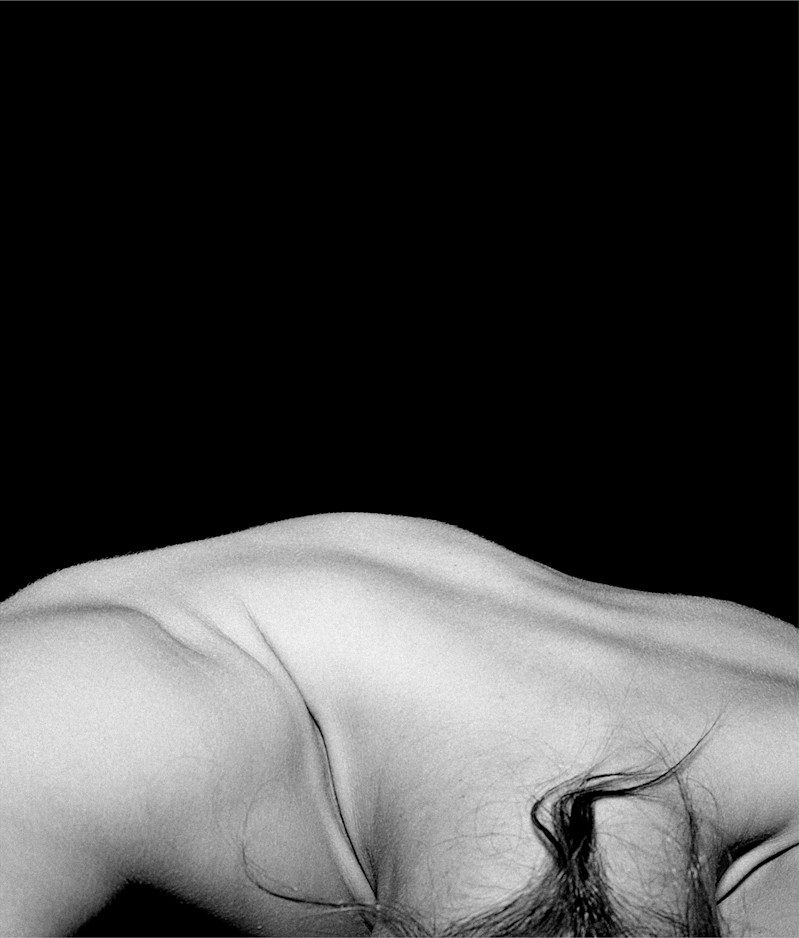

One day, I met the manager of Institut nationel de l’audiovisuel, in Bry sur Marne, just outside of Paris. He was very impressed with my technique and encouraged me to experiment. “Take pictures of yourself,” he said. I began trying things out. How would I go about taking pictures of myself? You see, I wasn’t making portraits, or self-portraits, or nudes. I was inverting the perspective, placing the mental focus in front of the camera, rather than behind it. It was about the body, not about looking into the camera. These pictures would never have worked if I’d been looking into the camera.

Every day, she took new pictures, in new positions, trying new angles. Every day, in the same place, with the same lighting. To achieve depth of field, she used an amateur’s flash, and halved the developing time. Entirely new sides of the body, which had always been there, but which nobody had seen (just like the surface of the moon!). She showed the results of her work. Without even really knowing it, she had achieved a radical shift: the third angle.

In 1976, photographic art was not the natural mainstay in museums or galleries that it has since become. A gallery, Galerie Régine Lusson, not one of the more famous ones, took the plunge and produced an exhibition of this 29-year-old Swedish woman’s remarkable pictures. Word soon spread. How could a body be so beautiful, and yet so alien and repellent? “A heraldry of the body,” “the photographic revolution,” “naked, vivid sensibility,” “Une rupture totale,” as Le Figaro and Le Quotidien de Paris put it.

One interesting episode during the opening of the celebrated exhibition at Régine Lusson was her encounter with Christer Strömholm, which finally happened. Suddenly, there he was! “I know you,” he said. “I’m the one who told you to go to Paris!” Eva Klasson let the fact that this wasn’t strictly true slide. They would go on to become friends, and it is said that Eva Klasson’s pictures meant a great deal to him.

She’s often been asked how she arrived at her method:

The camera can give you so much if you push it to its limits, and take it into a kind of no-man's-land, where you have the camera function in ways that the general consensus says it simply can’t. The camera shows something you don’t see. It seemed natural to use myself to demonstrate the physical awareness of the body. I concentrated in front of the camera rather than behind it. This meant that the camera was revealing, rather than depicting, as it does when you look through the viewfinder. I had some amazing surprised in the darkroom. I used a Nikon F and a simple flash that made the pictures almost clinically sharp, which was unusual in those days.

The art critic at Le Figaro, the acclaimed writer, critic, and curator Michel Nuridsany, who would discover Christian Boltanski, Daniel Buren, and many other names that would set the agenda for the 80s, wrote that her exhibition was extraordinary, and that it was like a paving stone hitting the surface of a placid lake (“qu’il fait l’effet d’un pavé dans une mare bien calme”). Jean-Luc Monterosso, who is now one of the most important names in French photography, was working at Le Quitidien at the time. He wrote: more than anyting, Eva Klasson reveals how photography is a receptive surface for unexpected creativity. A photographic revolution. Soon, a luxurious edition of the pictures was published, and they were included in an exhibition at the recently opened, radical Centre George Pompidou. Other successful exhibitions in the following years include Parasites(about pain) and Ombilic (about eating and digestion).

New Thesis on Eva Klasson to Be Published Soon

PHD student Lotta Granqvist is currently writing a new doctoral thesis on Eva Klasson. Her main focus lies with an exploration of Klasson’s method as avant-garde and conceptual in relation to the European 70s feminist avant-garde, and an exhaustive analysis of all of her works, not just the three series that have been published so far. There was also an earlier thesis on Klasson’s works published in 2013, which was written by Maria von Schantz Tylestam. This biography is based on documentation provided by these two researchers.