The glory of nature and the universe Isak Hall interviewed

Interview

September 11, 2019

- Paulina Sokolow

In the silent, mysterious, and abstract landscapes of Isak Hall, shifting ultramarines and ochres transform into distant vistas of the universe, where the laws of physics are completely different.

What is matter, what is stuff, or an optic phenomenon? Using old techniques borrowed from the great masters of the Renaissance and the Baroque, he explores painting’s potential by uniting different colours into new ones, having them fade in and out of one another on a single surface, or separating them with varnish to make a brighter colour seem to shimmer over a darker background. From the most delicate of gossamers to a solid mass protruding from the surface.

While these classic techniques were once used to depict the sparkle of jewellery, the blue cloak of the Virgin Mary, or the sheen of a suit of armour, Isak Hall uses them for their own sake, fully detaching them from any religious tradition or ancient mythology. The majority of the works he’s showing at CFHILL were created during the summer of 2019, which he spent in his studio in the northern hinterlands of West Bothnia. They’re painted in the glow of the midnight sun, a light so mythical that it’s tempting to think he’s actually captured some of its magic in giving his panels their luminescent glow.

What was your vision for this exhibition at CFHILL?

“I can’t really say I had a vision as such–my paintings simply come out of the act of making them, from the craft itself. I can’t rationally decide how they’re going to end up ahead of time. This time, I made an emerald series for CFHILL. Perhaps because morning light from the East tends to amplify green and teal hues? And because the windows of my new summertime studio face to the East?

I’m glad that you’re exhibiting drawings and watercolours from my collection along with my paintings. After all, drawing is an important component, and it plays a fundamental role in my painting. Over the last few years, I’ve been developing my drawing technique, which is partially inspired by symbolists like August Strindberg and Odilon Redon. You could say drawing on paper has guided my exploration of the consequences of illumination and the perceived dichotomy between light and dark.

For a long time, I’ve been thinking that I want to make a series of large-scale tempera paintings, and I’ve been able to do that now thanks to the grant I was awarded by the Swedish Church last year. I’ve given the series the working title The Temple Series, like Hilma af Klint’s series. Not that I’m thinking about her works specifically–it’s more that I’ve been thinking about what I’d want to paint if I was to make an artwork that could be hung in a temple. Something that precious. I mean, in purely symbolic terms. Like an artist being asked to paint for God during the renaissance. The series is also inspired by the Isenheim altarpiece, a set of paintings made by the renaissance painter Matthias Grünewald (1470–1528).”

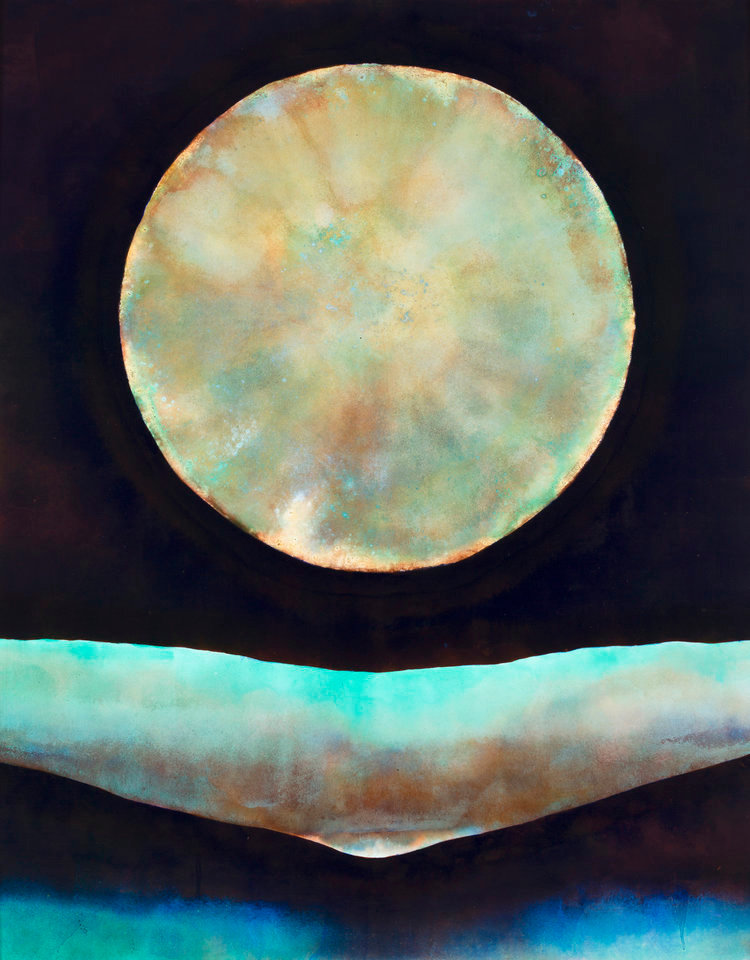

Isak Hall Untitled, 2019, Tempera and oil on panel, 160x 132 cm

Are there any similarities between this series and the Isenheim altarpiece?

”Yes, particularly the left panel: it’s like a halo surrounding Christ, a glowing light, more like an optical phenomenon behind him than a conventional halo (Ivan Aguéli claimed that God is light)–it’s like a spectral analysis of the halo, using emerald, and as it falls, you can make out an ultramarine sheen. I’d bet it was awe-inspiring in its day. Looking at these paintings brings me back to the landscape. My art is about the landscape. Landscapes, maxims, and religion are all somehow connected. There is a horizontal line that goes on and on, it’s represented by a curve in my paintings.”

Do you often take inspiration from older paintings?

”Yes, both in terms of their materials and their methodology. The paintings are also based on a fairly strict linear renaissance perspective, while the size is a reference to a French standard that was fixed in the 19th century. I think that a format more suited to the figurative will add an allegorical dimension to my works, allowing them to be interpreted as landscapes. In future, though, I think I’ll be doing more baroque-style painting.”

”My art is about the landscape. Landscapes, maxims, and religion are all somehow connected. There is a horizontal line that goes on and on, it’s represented by a curve in my paintings.“

Your new series is dominated by shades of teal. Tell us more about that.

”I’ve used two different pigments. One of them is ultramarine, which has been used in art and decoration since Medieval times. The pigment used to be extracted from a gemstone called lapis lazuli, which can be found in Afghanistan and other places. It was shipped across the Caspian Sea to the West and to Venice, where it fetched a very high price. The other pigment is chrome oxide green, or emerald green. I think paint manufacturers try to tempt artists with imaginative names–the one I use is called vert émeraude–it has incredible glazing properties, that produce an almost hallucinatory shimmer. The emerald also has the effect of enhancing the rustiness of the sienna. It becomes like an interface between the earth and the ocean. The point where enters, the moment of animation, when something is given a vascular system, a heart.”

The location where these works were made simply can’t be disregarded. You paint in natural light, in the hinterlands of West Bothnia. How do you think this has impacted your painting?

”Well, much of the inspiration for my works comes from spending long periods of time in the North of Sweden. There is very little light or noise pollution there, and the rationalisation of forestry has allowed me to study the midnight sun and the August moon from my shack.”

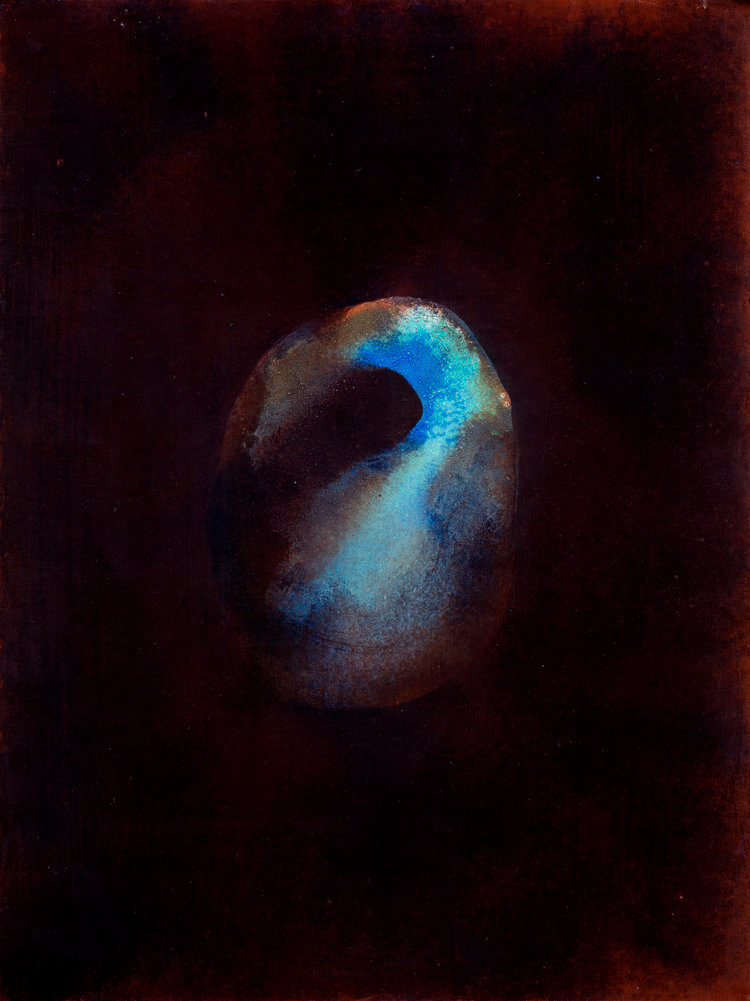

Isak Hall Untitled, 2019 Tempera and oil on canvas 60 x 45 cm

Is your art about the vulnerability of nature?

”No, I’d say it’s rather about the glory of nature and the universe. I’m thinking of the underground world, minerals and earth, rocks and caves, precious but toxic substances. I imagine that my art strives to depict something that lies below the threshold of consciousness. The thing I’m exploring and trying to construct is something absolute. It’s a cosmology of the existential. Our material origins, and ultimate reality. Our quest for the inscrutable. The fact that all is one, and the comfort this can actually give. One of the works in this series is titled Trust in the Universe. Nothing really matters that much. Everything will continue with or without us. We’ll just become a layer of the tectonic plates that are grind against each other. Eventually, all the stars, and all the light, will go out, and the universe will be dark for all eternity.”

How do you achieve so much depth in fairly abstract paintings?

”I’m always trying to refine my painting. The tempera I use for the underpainting has the property of giving a sheen that reflects outwards, while glazes made from resins and oils give an internal sheen to the painting–layer upon layer of transparent pigments wrapped up in semi-dry varnish. That’s how Rembrandt did it. Or rather, that’s how his assistants did it.”