The End is Near: On Adam Ytterberg's Torun och Farmor i Naturminne by Alida Ivanov

Essay

January 12, 2023

- Alida Ivanov

I don’t know about you, but I enjoy a dystopian end-of-everything tale as much as the next person. But sometimes they hit too close to home. In Torun och Farmor i Naturminne [Torun and Grandmother in Nature-memory], Adam Ytterberg tells his story through text and a series of paintings. It’s a satire that deals with our impending climate crisis, but as always in these types of stories: where does the satire end and reality begin?

Torun and Grandmother are going on an adventure. In this world, all the plants and animals have disappeared from Grandmother’s farm, and Torun decides that they will try to find nature once more. The pair arrive in a town called Naturminne, where all the plants and animals sleep while waiting to come home again. But Naturminne turns out to be a strange place. Torun and Grandmother’s attempt to get back home is, to say the least, a loopy and entertaining ride.

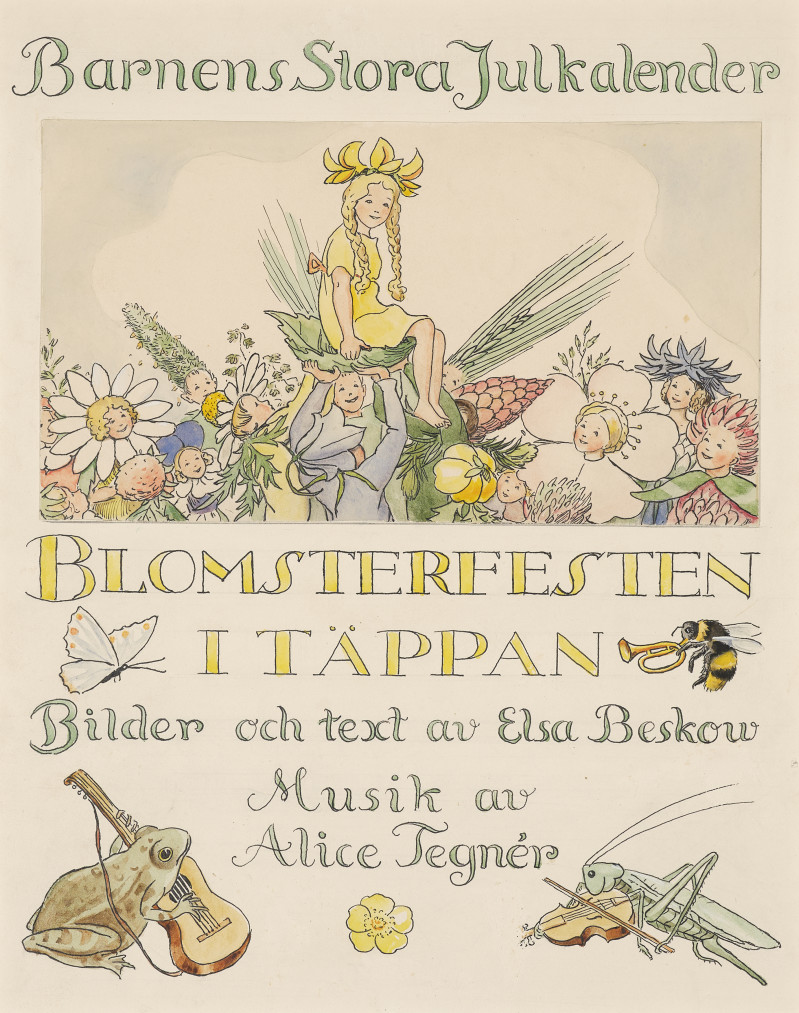

The suite consists of 10 oil paintings in various sizes, spanning from the smallest at 40 cm to the largest at 210 cm. Painted layer upon layer and with intricate details makes their creation both contemplative and time-consuming. The oil adds depth and shine to the different scenes we are met with. The colours are warm like the different nuances of fire: reds, oranges, and yellows with blues, and purples. This warmth can be related to paintings like Anders Zorn’s Badande kullor i bastun from 1906, in which the naked bodies emit out a sheen that almost jumps out of the canvas. Adam Ytterberg mentions Swedish artist Jenny Nyström, famous for her imagery of gnomes. He specifically points to a painting by Nyström called Konvalescenten from 1884. In it, we see two girls, one standing, and the other lying in a chair looking out into nowhere with a glassy look. The title refers to someone who is sick or on the road to recovery. The girl in the chair is sweating, the warmth of her skin palpable to the viewer. Every object is a symbol. Ytterberg works similarly with his composition: a story is told through the characters but also through the personal iconography of objects that inhabit the different scenes. Nyström’s world of mischievous gnomes is also present in Ytterberg’s, with their absurdity and fun but also darkness.

Torun och Farmor i Naturminne is in many ways connected to the calamity and decadence of Weimar-era painters like George Grosz or Otto Dix. The New Objectivity/Neue Sachlichkeit movement was a reaction to Expressionism. Even though there are differences, there are similarities too. We can see a similar shift today: the Post-Internet abstraction of the ‘00s and ‘10s has led us into a more figurative era. What we have in front of us is murky and unknown. Torun och Farmor i Naturminne captures the caricature style of Grosz and Dix (and many other New Objectivity painters) always balancing between funny and distorted, much like the characters in Ytterberg’s story, capturing hopelessness.

There are links to classical fairy tales that often are foreboding and cautioning or instilling morals and ethics into the young reader. One that comes to mind is Frau Holle by the Brothers Grimm, a fairy tale of good and bad, in which natural phenomena are anthropomorphised, or explained in a simpler way; in this case Frau Holle creates snow. The main characters Torun and Grandmother live on a farm and go on a mission to find all the disappeared animals and plants. Grandmother reads a story about a magical place called Naturminne and they wonder if it exists. Like the protagonists before them, they search for the portal to this new world. They find it and discover that it is now a mere hole in the ground, but they climb into it and enter Naturminne, where they meet Moder Gnista, based on the real-life nun Mother Christa. But in this story, Moder Gnista is more like Frau Holle and exudes the energy of being both kind and punitive. In Naturminne Torun and Grandmother discover lush greenery and Moder Gnista shows them around. They meet different characters like Gravänder [grave ducks, in Swedish the duck is the same word as the spirit: anden]. This is where they also find all the animals and plants that have disappeared from their world.

Moder Gnista continues the tour and which ends at a large and strange building in the middle of Naturminne. Well inside Torun and Grandmother realise that it houses a large oak tree called Stora Tickan, which will be the vehicle that will transport them to a new world. The many funny and absurd details in each painting hide the truth as a cataclysmic entirety. Naturminne is a doomsday cult (KIDDING, not kidding). Ytterberg follows in many ways the format of picture books for children, but with a darker undertone; much like in the tradition of Edward Gorey, or Angus Oblong, whose characters touch on subjects like death, sexuality, queerness, and mental health spelled out in a simple and facetious way. In this case, it lessens the blow of the world ending.

Adam Ytterberg previously worked sculpturally, even though painting has always been there too. He would then use text to describe or explain the different parts that would make up the sculpture. Much like his paintings, the sculptures build on personal iconography and objects from everyday life that are hidden in the wholeness of the structure. He utilises text as the first step in his process, a scribble of what is to come. In Torun och Farmor i Naturminne he started with texts that would describe each event, character, and place in the story.

Then for each finished painting, parts of the texts would be taken out. This type of process creates layers that you can go in and out of. The further along the process, the shorter the texts would become because the images would say more and more. But this also creates friction between image and text, where the text is not always caught up and the paintings have a life of their own. Absurdity resides in this friction.

The absurd. It’s the only way out of this. Adam Ytterberg captures the zeitgeist. The world he has created is colourful, engaging, and exciting. You’re drawn into it and want to know more. It also tells a story about something important that we need to change now, even though it might be too late.

Adam Ytterberg (b. 1991 in Strängnäs, Sweden) is an artist based in Stockholm. He is currently completing his MFA at University Arts, Crafts, and Design in Stockholm and will graduate in 2023. A way to describe his process is slow painting: the largest taking several months to make. His style is distinguished by the richness of colour and detail. Previous exhibitions include Painters’ Salon, Mollekyl Gallery in Malmö, (2022), Sörmlands Museum, Nyköping (2020), Konstnärshuset, Stockholm, (2019), Liljevalchs, Stockholm (2017), Swedden. Ytterberg was the artist-in-residence at the popular interactive play Satans Demokrati in 2016 and received The Swedish Arts Grants Committee's work scholarship in 2020.