Mats Gustafson — Interview by Erik Galli

Interview

November 21, 2019

- Erik Galli

Mats Gustafson’s oeuvre is marked by conflicting desires. Born in the countryside and surrounded by nature, he longed for urbanity. His fashion illustrations were born from this desideratum; in turn, they are what started his career. His later work bears witness to a reversal: a yearning to return to nature once more. In the mid-90s, after spending a decade in the bustling art and fashion scenes of Paris and New York, Gustafson left Manhattan (though his partner, jewellery designer Ted Muehling, kept his downtown apartment) and moved to the village of Sag Harbor, Long Island. From his house and studio Gustafson paints swans, deer, and landscapes. More comfortable observing than participating, he’s finally come full circle: far from the stress of the city, he’s at nature’s doorstep once more.

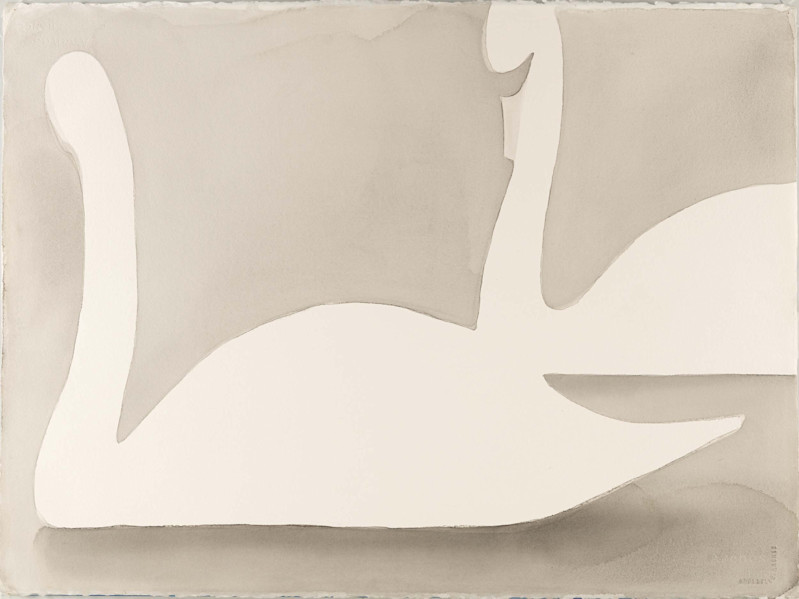

Gustafson doesn’t paint extraordinary motifs; a single swan, the head of a deer. The silhouette of a lone spruce, dark against the crepuscular sky, echoes the Swedish 19th century master Carl Fredrik Hill’s Ensam gran på fält (Solitary Spruce on a Field). When picking out trees to model for him, Gustafson doesn’t go for the most beautiful. Trunks stretch upwards, starved for light and thin from growing quickly and densely together. Branches and leaves are done away with, the trees reduced to lines and fields; to Gustafson, details are distractions. In his series Rocks, each stone inhabits its own painting—there’s nothing else to compete with. The rock regards itself, reflected in quiet water, relaxes, and lets us in to admire its surface, texture and shape. Stripped of its context, the rock is present.

Fashion illustrations still make up the bulk of Gustafson’s work. His women, painted in ink or watercolour, drawn in crayon, or cut into collages of coloured paper, are free, fast, and in many ways antithetical to what Gustafson calls his “free work”. While his paintings are timeless, his illustrations are time documents, each outfit a reminder of a season and a year. Gustafson expertly captures his women in movement, clothes flowing around them on invisible runways; his landscapes—foggy shadows reflected in monochrome lakes—are perfectly still. This dichotomy is no coincidence. When thinking back on the years in his Manhattan apartment, Gustafson recalls missing the sight of trees when looking out the window. The attention to detail in his art reveals a yearning, a kind of devotion reserved for things we long for but don’t take for granted. Gustafson’s love of nature and of the urban feed and inform one another, each providing fuel when he works with the other.

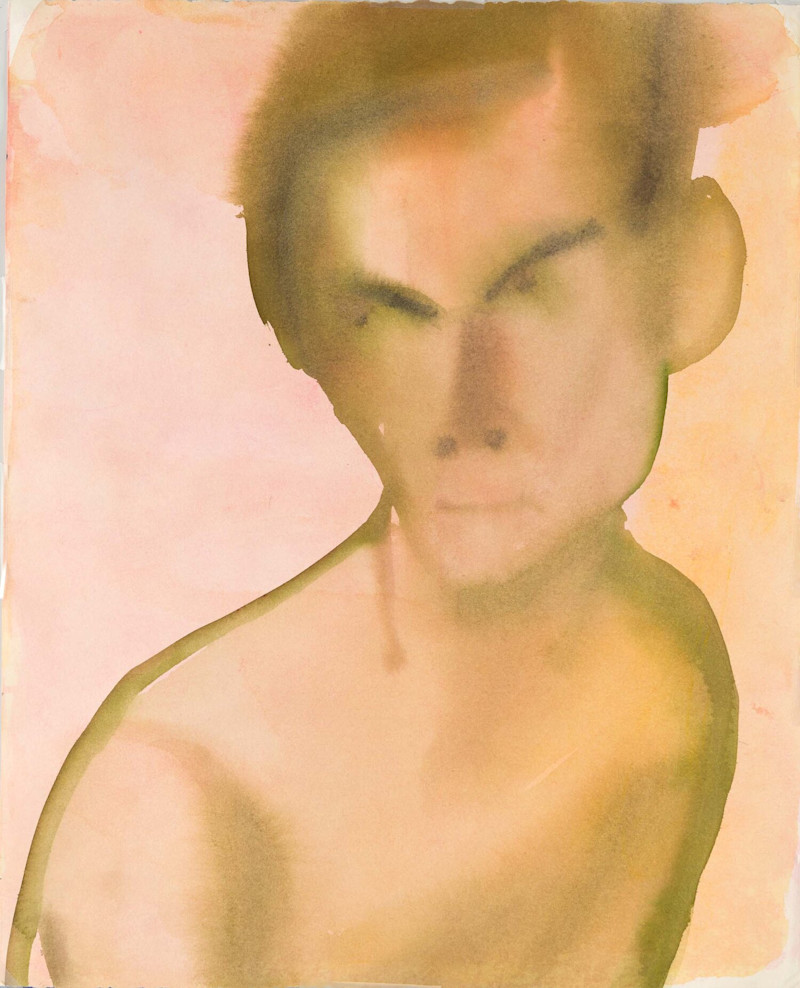

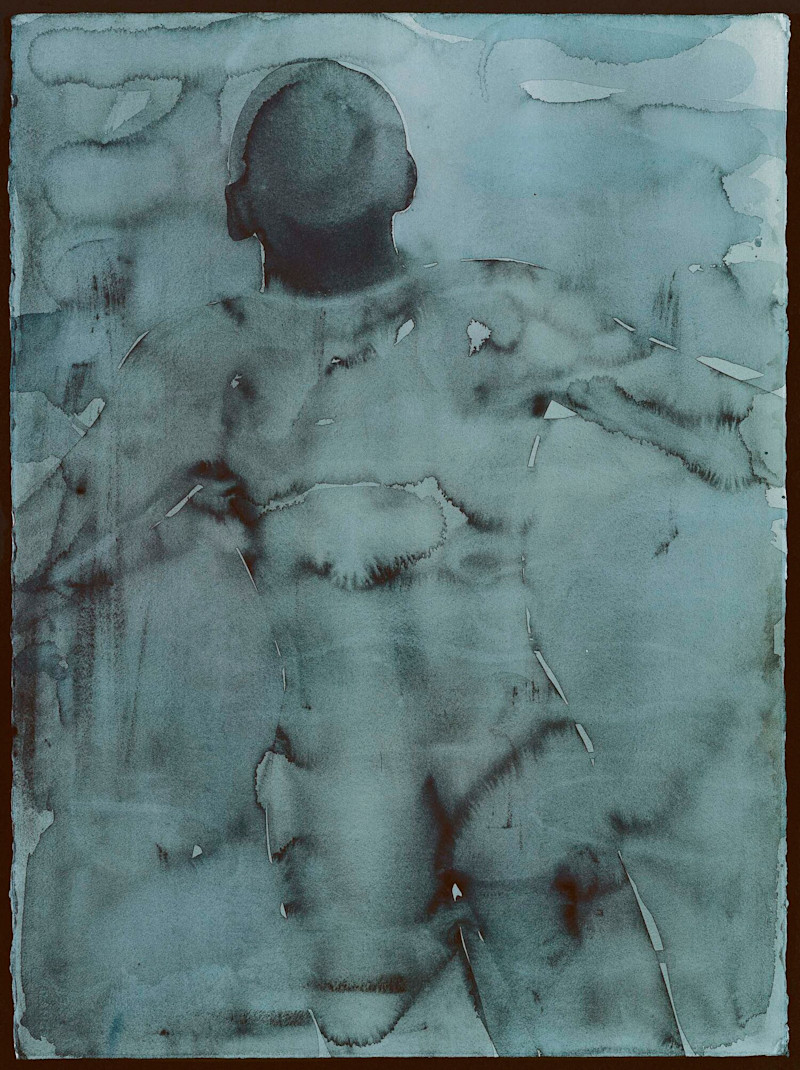

Gustafson is on a quest for beauty—beauty as emergent from a process of simplification. What he finds is something instantly recognisable, yet diametrically opposed to hyperrealism. Nowhere is that clearer than in his portraits and nudes. Gustafson gently but precisely uses his watercolours to capture an accountant, a cleaning lady, a partner, or a celebrity. Affectionate and painted in warm hues, these portraits share a sombre set of siblings. When the AIDS crisis engulfed Gustafson’s world (among those he knew who tested positive was his boyfriend at the time), the response became his first public departure from fashion. From his need to deal with the losses sprung a series of male nudes—dark and suggestive, painfully intimate. This series, controversial at the time for its theme, became Gustafson’s first solo exhibition, shown in Stockholm in 1995. The men have no faces, but we still see who they are: a friend, a lover, a loss.

Gustafson believes that if you look hard enough, you can identify something’s essence. Regarding one of his subjects is akin to envisioning it instead of seeing it with your eyes. This is Mats Gustafson’s gift: to tenderly draw out the beauty that resides in the ordinary, and make us recognise that we’ve known it all along.

Mats Gustafson Karl 1, 1991, watercolour

Your career is often described as beginning with your fashion illustrations, in the late 70s or so. What were you making before that?

— Probably a lot of people and clothes, actually. I’ve always enjoyed clothes—and history. So not just contemporary clothing, but costumes, too.

You attended the Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design and then the Dramatic Institute. Did you always have this interest in fashion?

— Absolutely, I’m sure it’s always been there—but I never considered it as a career. I’d decided to become a scenographer, which is why I attended the Dramatic Institute. I never studied fashion or fashion illustration, but I was always doing it privately. My work got published in a Swedish magazine, and I started working with H&M. I realised that this was exactly what I wanted to do. At that point, I’d been doing my free work for a couple of years as well.

Looking at your earliest nudes and portraits — some of your first departures from fashion illustrations —they’re quite different from your later work. There’s something almost reminiscent of Picasso in them.

—Yes, maybe you’re right. There are a lot more lines—thick ones. These were my first attempts to move away from fashion. Picasso and Matisse were very present to me then—they’ve inspired so many for generations.

Male nude, 1994, watercolour, 76 x 56 cm

In what you now call your AIDS suite, just a year or so later, the lines are almost gone—only the fields are left.

— Well observed! I found my own way of working.

To me, those paintings stand out in relation to both your prior and later work. I experience many of the women you’ve painted as stylised, as ideas. When I look at these men, they feel like real people. They’re so close.— It was very important that they be intimate. And the fact that they were men changed something, for me as a gay man. And yet, I know all of these women personally. The culmination of the AIDS crisis was so prevalent in the art and fashion world. I was so surrounded by it. This was a way to channel it, to work through it.

The portraits of your parents and relatives also feel very intimate.

— Yes. My parents were getting old, and I wasn’t young anymore, either. Fashion is so connected to youth. Age was something I’d never had to work with. Fashion mustn’t have age—if it does, it’s not fashion anymore, or it’s the fashion of yesterday. I wanted to work with something emotional—but also something more technically challenging.

Watercolour is such a capricious medium. In spite of the minimalism of your works, you manage to retain your subjects’ features. One drop of water too many and they could be distorted.

— Indeed. I have to work with an element of chance, trying to control it. I work very fast. I don’t sit and mess around with anything for too long—I make a new image, and then another, and then another. I often end up with long suites of paintings. Many end up in the trash, but sometimes more than one of them hold up, and have their own value.

Are you interested in the purely technical?

— Not really, no. It’s a necessary evil, a tool. No one taught me watercolour technique. I learned through my own mistakes. I’m always in a hurry and always have something I want to bring out. Watercolour works well for that. I’m no virtuoso, but I want my own expression to come through. I want my hand to feel present.

Your work suggests a longing both for the urban and for nature.

— Having grown up in the countryside, I wanted to flee towards something much more artificial and glamorous. In hindsight, I’ve understood the impact being close to nature had on me. Nature plays a very big role in Swedish culture, I think—taking it in, enjoying it. My nature paintings came later, as a reaction to urbanity. They contain a longing for nature. I’m not trying to depict it, but rather an idea or a reminder of it.

There’s another duality in your rock paintings. You treat all your subjects with a lot of tenderness. Isolating something to give it your full attention is an act of love, but there is also something humorous about doing it with a rock.

—You’re the first to say that! The tenderness, naturally, is something I want to show. In my fashion work, there’s none. I find fashion interesting, and I want to display it—but not tenderly. I don’t try to explore who the woman is, or even what she looks like. It’s a female being, who I feel affection for, but the protagonist is the garment. When you simplify, you’re forced to consider how you relate to the isolated subject. Most people can read a rock, and might see it as poetic, beautiful. It’s lovely to hear that you find humour in it. That means I can do it a while longer!

Speaking of beauty—do you look for it in all your work?— In terms of trying to see it objectively, yes. I’m driven by a need to find it. But because so many have done it before, ideally you want to see the beautiful rendered in a new way. Swans, for example, are almost taboo—they’ve been portrayed so many times that they’ve become banal. Still, you can’t escape the fact that they are magnificent beings. They’re also very linked to Stockholm. Say you’re taking a walk by Skeppsbron on a cold winter’s day. Pitch black water. And then the white swans. Magnificent! What can I say? To me, beauty is an experience big enough to be portrayed.

Mats Gustafson Swan 2, 2010, watercolour

Erik Galli is a cultural journalist, working for the Swedish Television (SVT), among others.