Liselotte Watkins in Conversation with Elin Unnes

Interview

June 3, 2020

- Elin Unnes

Liselotte Watkins is stuck at home in Rome, undergoing a second, involuntary period of house arrest: on the very day when Italy’s severe social distancing measures first began to be lifted, she took her Labrador pup for a walk, and when it jumped at her, she lost her footing and broke her leg. Meanwhile, her new exhibition for CFHILL–paintings and vases that have travelled alone through Europe, from Rome and Capri–is in storage in Årsta, just outside of Stockholm. We spend some warm days in early June talking to each other through a video chat, and Watkins shows me pictures of paintings of rooms. The interiors are sparse almost to the point of the sacral–like a monk’s cell–yet simultaneously gaudily cluttered–as though the monk had thought like a homey old lady when decorating his cell. The vases, in turn, often depict women. This is a symbolic subject, on several levels: in certain times, women were thought of and described as empty vessels, of no inherent value until filled with seed and, eventually–God willing–producing baby boys. This exhibition originated on Capri, at San Michele, a villa that physician Axel Munthe had built there around the last turn of the century. During his lifetime, Munthe was one of Sweden’s best-selling international authors, second only to Nobel laureate Selma Lagerlöf. These days, he’s mostly famous for his beautiful garden, his impeccable taste, and the legendary alcoholic monkey which he took over from a sea captain. This is Watkins’s fourth exhibition at CFHILL.

Could you tell me about this exhibition you’ve made?

Well, it’s a series of interiors. I began by… Well, the exhibition… Ah, here’s what happened: I was going to do an exhibition of pots. They were at Capri, because I had shown them at villa San Michele. That was the initial idea: a smaller exhibition of the vases from Capri. But then, CFHILL asked me if I would mind showing some paintings along with those vases.

Wait–was this an exhibition of paintings of vases, or of physical vases?

Physical vases. They were shown at Axel Munthe’s old home villa San Michele last summer. Then, they were sent to CFHILL, because we wanted to do a Capri exhibition.

But when we decided to show more than just the vases, I simply started painting. This was still the late fall of 2019, we still had plenty of time, and I started painting with Capri–which was still part of a free Italy at the time–in mind. As I worked, I was thinking of villa San Michele, and of these women. But then, as you know, the whole country shut down, and as time went by, the isolation only increased. It started quite early; we were reading about Wuhan… Back in January, even though Italy hadn’t yet closed down, I got the feeling that things were not going to turn out well. And this made me paint more and more, particularly interiors, and I started to create strange, vacant environments with no people in them. Then, starting in February, everything shut down. I immediately moved my studio back home. So, I began painting at home, and I carried on doing that throughout February and March… well, until a couple of weeks ago, really. I almost only painted interiors. It was all I had to access, after all.

And when you say “those women at Capri,” which women do you mean?

Kristina Kappelin (CEO and director of the Swedish cultural institution Villa San Michele) asked me to produce an exhibition to be shown in the gardens at villa San Michele. The garden is encircled by a pergola which is roofed at its centre, and that’s where Axel Munthe’s sculptures, which he hauled there from the depths of the ocean and other exciting places, are on show. I decided to round out his collection with all these women. I read up on Axel Munthe before the exhibition, and I developed something of an obsession for all these women that he supposedly cured from nervous dispositions–although he really did no such thing, of course. After all, there was never anything actually wrong with them. This gave me the idea of making a series of women on vases: upturned vases, with faces painted on them. They represented all these female socialites who I was kind of imposing on Axel Munthe, all over again. He fled for Capri with the express purpose of escaping them, after all. He got so damned fed up with them. They were such pains, all these high society ladies he met in Paris, and in Rome. He was great at curing them, because he got them to do stuff. They were really just bored, so when he told them things like “buy a dog,” or “don’t have sex with your husband,” they were immediately delighted and made lots of progress. So, I decided to burden Axel Munthe with these women one more time. I made an exhibition of vases featuring women, and placed them among his sculptures. It was lots of fun.

He took a pretty dim view of women, particularly in The Story of San Michele.

I think it’s a bit like with that philosopher. What’s his name? Was it Camus, Céline, or Sartre? One of those French chaps– everyone says he hated women so much. But then, he hated everybody! I think Axel Munthe was a bit like that. I mean, he liked... animals. He had his animals, his monkeys, his dogs, and he liked them. But I don’t think he was too big on people, and he probably didn’t understand women at all. And that book... well, it’s very old. Naturally, it is upsetting, but it was written one hundred years ago.

The only passage that I really can’t stomach is the bit where he states that “women can’t paint.” And, like, we know he hung out with Marie Krøyer!

That stuff is so difficult, because if you like that era–and I do, I love the turn of the century stuff... Even Gertrude Stein said that, you know: “Women could never, ever, paint like men.” I don’t think we need to make excuses for it, but we could take it with a pinch of salt. Maybe it was just jargon, or something.

Tell us about the paintings you’ve painted. Capri depicts a bed, a chair, a candle, and a clock.

It was the first interior I made–in January. I was reading a lot about China, how people were in quarantine, and the situation felt very alarming. That’s when I started painting interiors. I think it was an immediate response to the mood that was sweeping the world. La Tenda Rosa is also an interior, but I made it much later.

Bed, candle, clock, again.

And the woman praying, there above the bed: she’s praying for a better day. I think that was the last one I made. I was pretty fed up with the whole situation by then. So fed up, in fact, that I actually considered praying to someone. Religion is a recurring theme in these pictures, like in Pomeriggio, the one with the crucifix and the girl.

Are you religious?

Absolutely not. Not in the slightest. I’m actually very un- religious, if that makes sense. But I find religion fascinating. Living in Rome, where the Vatican is such a great presence, is fascinating to me. I’m not sure how many churches we have in Rome 20,000 or something–and it’s an aspect of life there that’s difficult to evade. In any case, I continued painting inte- riors. They’re all dusty, covered in a kind of film. A few wom- en make appearances, too, like in Pomeriggio (“afternoon”). Paulina at CFHILL saw a particular resemblance to one of Sigrid Hjertén’s women in that one. I was in a duo exhibition with Sigrid Hjertén in 2018, which included one of her more noted paintings. It depicts a woman who reclines nude on a bed, a red curtain, and there is some kind of explosion. Some have interpreted this as somehow representing sexuality. I’m not too fond of that particular painting, because of all the strange interpretations it has been subjected to–for instance, people have speculated that the woman in it might be her lover. I think I envisioned Pomeriggio more as a daydream, but since the sim- ilarity was pointed out to me, I can see it, too. Like the women’s poses: Sigrid Hjertén’s woman is looking at the red curtain, and this woman is looking up at the crucifix, on this warm, dusty af- ternoon. This vaguely claustrophobic dustiness makes all these paintings very Italian. But we’re also showing Tavola–which is large and in charge at 150 x 100–and in which I’ve included my vases. I made the large vase on the table in it a long time ago, but it was ruined. Something strange happened to it, and it cracked, so I let it live on through this painting instead.

It lives on in the astral plane of art.

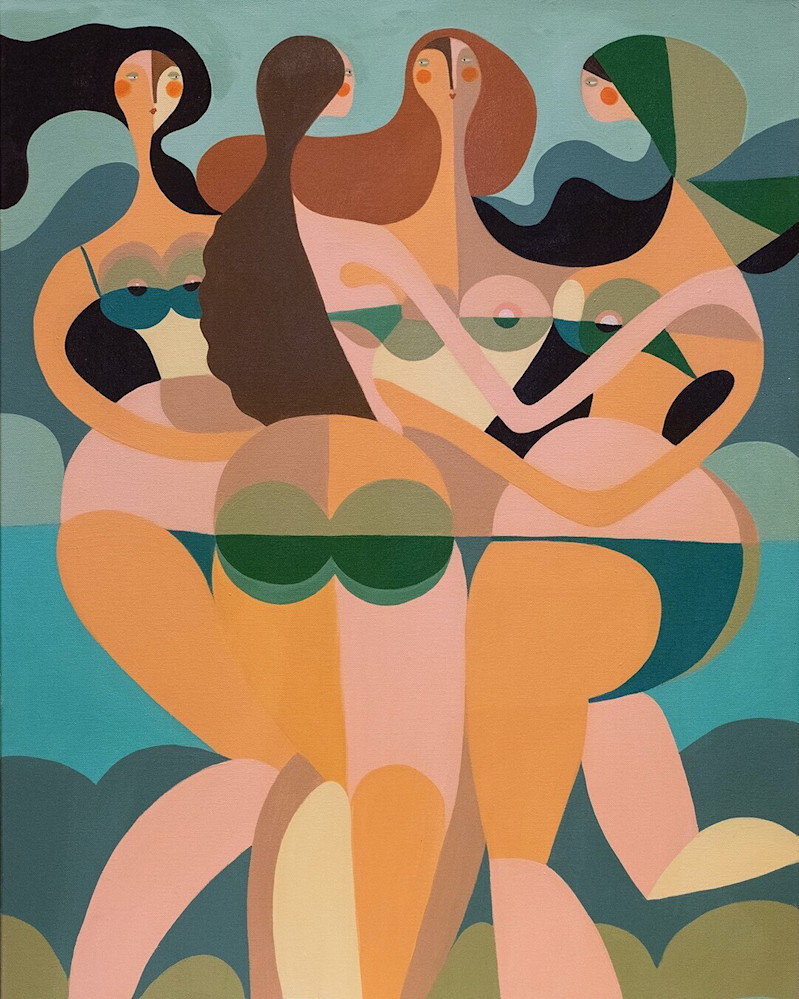

Yeah, it’s all very meta. Camera da Letto also has that almost religious mood. It’s something about how the white light enters it. Paura was the first painting I made. Paura kind of means... being scared. The painting depicts a seriously over-protective mother and her children: The mother is holding onto her daughter, who is also wearing a swim ring, very tight–she’s pretty sweaty, and her bikini has slipped out of place. This is something I’ve witnessed first-hand in Italian holiday spots, where mothers hold on very tightly to their children. Insieme (“together”) came about back in October, when my mind was still on Capri. Back then, the vases were going to live on, and the women were free. AnaCapri Natura Mor ta also depicts one of the vases from Capri–I gave it new life as a still life.

Hey, I just have to ask you something. Now, of course, everything doesn’t always have to be related to feminist theory...

No.

...but once, I was interviewing Saami glass artist Monica Edmondson. I said something like, “Oh, you make such beautiful vessels,” and she sighed, and said, “please call them something other than ‘vessels’...” You’ve gone the exact other way, and placed a woman on a... vessel. Is that deliberate?

Oh, most certainly! The reason why I started making these ceramic vessels, or amphoras, which is the Italian word for these vases with are used to store wine and oil and the like,

was that their shapes are so feminine. They are easy to convert into women’s bodies. Ceramics also happen to be very sensual, very delightful. When you hold them, they communicate a sensation: they go cool in the winter, and warm in the summer, they behave in various ways, they are living materials. I don’t make ceramics myself; I find vases that are discarded, used, unwanted. And then, I give them new life. These are everyday objects that aren’t even thought to be too beautiful–unless they actually date back to the Classical period and turn up in a dig or a museum. But what I’m doing, it’s a bit like painting women on saucepans, or something.

[left]

Lilith, the first woman, was made from clay.

Exactly.

Then, she was infused with fire–she was a clay woman who was reanimated and granted a second life, in free- dom, thanks to fire and magic.

It’s a beautiful story, and I love the symbolism there. Some of my vase women are more anarchic–some of them even look like they are about to break out of the vases. But the woman in AnaCapri Natura Mor ta is very content, as though she spent her life swimming around in her vase, almost like a goldfish. The vases are always rewarding to work on–the feeling the vase gives me influences the image I paint. But I like the way it’s both decorative, and not at all decorative. The interiors have that same quality: they are both decorative and pretty damned dys- functional. There is a claustrophobic side to them, but they are also pretty things somebody made. And they’re lonely: a chair, a plate. Like in Il salotto (“The Sitting Room”), with that closed door. In the earlier paintings, like La Scultura, which I painted in October–November, you can see a degree of happiness and life. The flowers on the table are still alive, and there is a joy to them that has died down in, say Da Sola, where things have taken rather a melancholy turn.

You can’t even see out through the window in that one.

Nope, it’s closed. The women in the small portraits on the walls, like in Da Sola and Pomeriggio, also tell their own stories. Portraits of family matriarchs are an ever-present phenomenon in Italian homes, like in Letto Singolo, for example–they’re always watching over the household and their domain.

You painted these claustrophobic interiors in some rather claustrophobic conditions. You mentioned a dusty quality, and when I’ve interviewed you in the past, you’ve mentioned your love for the housecoat, as a fashion statement. So, which is it: where you painting as a form of therapy, to process your claustrophobia, or did you enjoy it?

That’s the part that’s so contradictory. The thing I appreciate about Italy is the way the old is kept around: you can go to old trattorias, and there will be a woman in a housecoat taking orders. But at the same time, particularly as a Swedish wom- an, or, well, as me, at any rate, this can be an infuriating place, because nothing ever progresses here. Nothing ever changes, at least not in the proper way that it does in other places. Maybe

it does in the North, a little, but I don’t live in the North, I live in South Italy. But I’m also very isolated, and have been for the last ten years. The lockdown suddenly made it OK to spend time on your own, to stay at home, not see anybody, and just immerse yourself in work. Despite this, I’ve been surrounded by Italian voices. My temporary studio was a small room that faced the back garden. It was a busy spot. All the windows were open–it was already hot out–and I was served a generous daily helping of Italian family life; I could hear them all the time, as if they were in the studio with me. They found their way into the paintings and it all suddenly turned out incredibly Italian. I found it delightful. The Swedish stuff was nowhere to be found, and I was like a small part of something much bigger. Repetition and routine were the crutches I leaned on each day. In the afternoons, I would go into my studio and work on my paintings. And when it comes to painting, it’s good to be alone–it makes the work so much better.

Tell us about your work tools.

I let colour guide my work. I often have a colour selected before the subject and the palette fix the piece. I don’t grind my own pigments; I use existing paints and mix them to dirty or liven them up.

What kind of paint do you use?

I’m not a snob, and during this particular time... The only place that was open was my local Ferramenta.

A DIY shop?

Exactly. But remember, this is an Italian DIY shop: it’s old school. They have brooms and stuff hanging from the ceil- ings, and they sell everything. They stayed open even though everything else closed down.

I think DIY shops were considered essential, because they sell things people need to repair things in their homes, water leaks and so on.

I went there, and bought the acrylic paint they had, and then I mixed it with paints I already had. I was limited in every mate- rial respect, after all: paints, canvases, brushes. I had to use what I could find or already had lying around. Nothing was open. But this experience turned out to be rather pleasant, too. My DIY shop is in my own building, and I know them pretty well, so I started going there to buy paints nobody had touched for years. The tubes were all dusty, and they had a shelf all to themselves. Like, who buys art supplies in a DIY shop? And I found canvas- es that had been lying around back in their storage. That was a pretty dusty, pleasant experience, as well.

Well, this is completely wonderful! Your time in house arrest has influenced the works, in everything from their subjects to the colours used–even the way you acquired the actual materials!

I didn’t exactly have unlimited space to work with in the purely physical sense, either. Towards the end, I simply had couldn’t fit any more paintings, even though I had spread them out in the other rooms. This caused my paintings to shrink in size, too: I ran out of space. The first ones I made were 150 x 100; I had all the space in the world when I made Tavola. After that, I worked with 70 x 100. Then, 30 x 40, and the final ones were just 20 x 30. We were getting pretty cramped at that point!

It’s amazing to imagine you in your studio, painting away, pausing only to fold and cut canvases so that you can keep going.

It was a case of playing the hand you’re dealt. But to be honest, I like to keep things simple, humble.

In several of the paintings, there is a painting hanging on the wall. You’ve painted paintings in your paintings. Which means that you’ve also made miniatures; two paintings for the price of one, essentially.

Yeah, I enjoyed that.

Carl Larsson painted a lot of interiors, too; he painted his own home, where his own paintings hung. So, he painted his own paintings. Have you painted your own paintings? No. But I have painted my vases. In Tavola (“the table”), there is a plate I’ve made, and the vase is mine, too. I enjoy repeating myself, and taking things I’ve already made as props. I think that’s how Carl Larsson saw it, too. I’m sure it was Karin Lars- son who hung the paintings and made the decorations in his home–she designed the interiors, right?

That’s right.

In the interiors, he was portraying their lives. There, the painting is no longer a painting, no longer some big, great work of art–it’s just a part of a life. Of the life they shared. He seems very much like an observer of a world to me.

Do you feel like an observer of worlds?

Creating little environments has always given me a sense of security. Since I was very young, I’ve been going to auctions, buying and trading stuff, and redecorating our house in the country. I could get an idea, and move my parents’ bedroom to the recreation room, and give myself a new room. I wasn’t the happiest of children, but creating environments gave me a sense of harmony. I’m not really interested in interior decoration, or objects, their prices and whatnot. But I am interested in what they can do.

That makes painting them a clever option.

It also allows me to create things that aren’t there. It turns painting into play, and I think this is the first time I am allowing myself to play.

These paintings are quite different from the things you’ve done in the past.

Yes, it all happened quite naturally. Just think how many years I spent drawing–and all those years, I was drawing “pretty”. Now, I let go of all that, and began to work graphically, abstract- ly, instead. The women turned into shapes, the environments turned into shapes, everything was broken down into some- thing that began to approach cubism. Then, I let go of that as well, and focused on the colours and the language of colour. I was never really very good at dimensions and perspective, after all. These environments look very strange. I didn’t use any originals, or sketch anything out in advance; I simply worked directly on the canvas and came up with the settings as I went. You see, the moment I start to draw on paper, I find myself stuck drawing pretty again.

Switching mediums is like a magic trick. It’s like writing an article, as opposed to a blog post or a book. I’m differ- ent people when I do those different things.

Besides, I was painting inside a bubble. I didn’t give a single thought to what would happen afterwards. That’s always the trick: never focus on the end result, always focus on the moment.

So, what are you going to do now, in this moment?

I’m going to go visit my doctor and see if I can convince him to take my cast off ahead of time.

Good luck!

Thanks.